Perhaps the most critical element in a successful marketing campaign for a co-op or condo unit is the price. Well, how is that price determined? What factors are considered? Whose expertise is needed to arrive at the optimum number? Is conjuring up that offering price an art or a science?

Science Versus Art

“I think it’s more of a science than an art,” says Joanna Mayfield Marks, a broker with the New York-based firm Halstead. “That doesn’t discount the artful part, though. Condition is the artful part. That’s why we do staging, which can make a huge difference, especially in certain neighborhoods. When location is prime, the artful part of pricing really comes into play. But when the apartment is in a high-volume location and there’s a lot of inventory, sellers are taking a scientific approach and looking for value.”

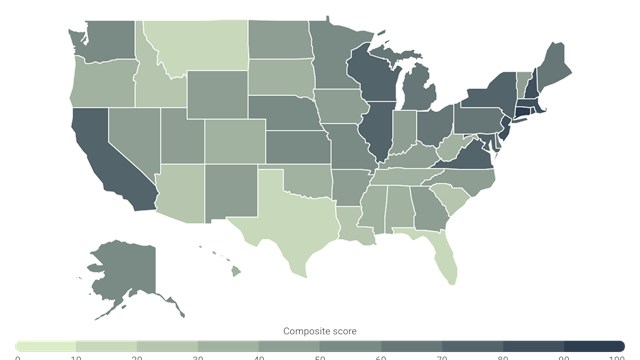

Jonathan Miller, President and CEO of Miller Samuel Inc., a New York City real estate appraisal and consulting firm, believes pricing and valuation are a combination of both science and art. “I despise each definition on its own,” he says, “because it’s not strictly either. There’s a lot of gray area. And the gray area is how someone with experience navigates what’s subjective. That’s what separates someone who is good at valuation from someone who is not.”

Ryan Hardy, a broker with Gold Coast Realty in Chicago, believes “it’s a little bit of both. But I lean toward pricing being an art. There’s data that goes into it as far as recent sales in the building are concerned, but the actual final pricing is determined by things like staging and condition. Some units show really well, others don’t. The science is in using the data, but any premium you get over that is an art.”

‘Location, Location, Location’—Not Anymore

The age-old axiom in real estate was ‘location, location, location.’ According to Marks, that’s no longer a singular truth. “It’s price, condition and location. You can’t change the location variable, so we take that off the table. Condition can be changed. We work with that. In the end everything sells. In the end, it’s price.”

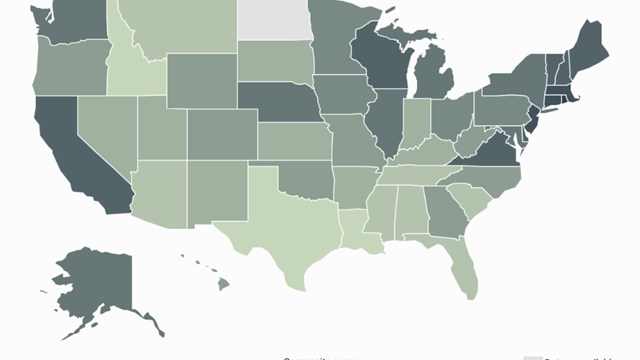

In Chicago, Hardy explains “location is always the biggest factor,” although other considerations such as condition, and in particular views, come into play. “It almost doesn’t matter how nice or what amenities the unit has.” He says there is a clear correlation between distance from downtown and prices. The longer the commute, the lower the price.

The Difference Between Price and Value

“A common question I’m asked,” says Miller, even before he sees a unit or does any research, is “‘So off the top of your head, what do you think it’s worth?’” That’s an impossible thing to answer for any appraiser, or for that manner any broker, undertaking a sales pricing estimate. While the two are not the same they are predicated upon the same methodology, the comparable sales approach to value.

The comparable sales or market data is one of three approaches to value employed by appraisers to determine the worth of real property; the other two are the income approach and the cost approach. “Anyone valuing something that’s not an investment property will almost exclusively use the market data approach,” says Miller. He goes on to explain that “a comparable sale is something that a fully informed buyer would consider as an alternative to the subject property, actual competition. More often than not when someone supplies you with comparables, they are sales in the subject’s neighborhood that have little or nothing to do with the subject property. The nuances between the comparables and the subject then require adjustment.” These adjustments can reflect improvements, views, light, etc. The comparables are adjusted to equalize these amenities and arrive at a value estimate.

For appraisers, potential comparables can be broken into three groups: closed data, contract data, and listing data. Closed data lag behind the market, contract data are hard to verify, and listing data represent the upper end of value. “Generally speaking,” says Miller, “a listing price is structured to encourage negotiation, so it’s usually a little high.” The difference between listing prices and actual values then reflects the art with which listing brokers seek to market property, as well as the science of the reality of the marketplace.

Establishing a Price

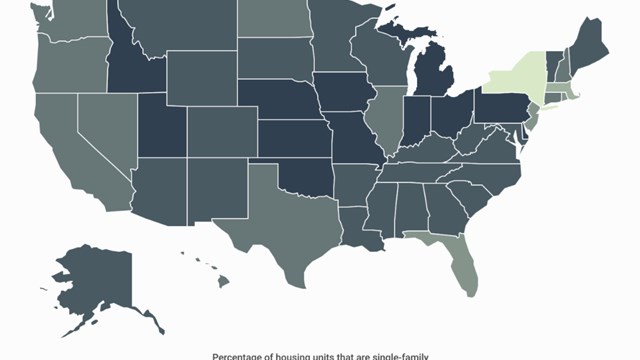

“We look at amenities,” says Marks. “Does the apartment have a doorman? Is it near the park? Amenities come into play in particular in elevator buildings. There is a cost associated with having amenities and monthly charges are higher. Transit access is also very important. Buyers like to be closer to the subway and close to multiple lines.” A thorough examination of these factors and comparison to recent sales, preferably in the same building, will help a listing broker determine an asking price. Like an appraiser, a listing broker must have an ear to the ground.

“With an existing property,” says Hardy, “in a condo or a co-op, typically there are tiers in the building and, for example, the unit on the eighth floor is the same as the one directly above or below it as far as square footage or basic layout. With that in mind, buyers look at the units above and below, if they have sold, to determine the value of the subject unit. When there have been sales, buyers go off that data.” They will adjust for things like views and condition. “That’s where the ‘art’ comes in. How much is the unobstructed view of the lake on the higher floor worth? With new construction, you compare other similar, newly constructed units in the area, rather than just the building.”

The “One-Buyer” Theory

During the real estate recession of the early 1990s, a new theory of selling real estate became popular. It was known as the “one-buyer” theory. It is attributed to Barbara Corcoran, founder of brokerage firm The Corcoran Group and one of the cast members of TV’s Shark Tank. The theory maintains that rather than chasing a falling market by dropping your offering price to get ahead of the slide, sellers should hold their price, because each unit is unique and there is a single buyer out there for each one, given enough time and exposure. This theory goes against every established method of valuing real estate or pricing for sale.

“When a unit has a certain look or style that sets it apart,” explains Marks, “there might be a single buyer. But overall, buyers in New York won’t do that. New York City buyers are incredibly sophisticated and savvy. They can’t be played with. Selling ‘the emperor’s new clothes’ won’t work. Take a scientific approach. However, if you’ve done a unique, terrific renovation, and a similar unit has not had the same treatment, we can show buyers what they’re getting with that unit.”

“If you have the luxury of time,” Hardy says, “there’s always a buyer out there. But for most people that’s not the case. If you want to sell you need to price the unit right.” He relates how he took over a listing that had been on the market for over six months in a luxury high-rise. The price was simply too high. He went to meet with the sellers with the appropriate data and they agreed to lower the price. The apartment sold in two weeks. They might have agreed to that price earlier, but the listing price was so high no one made any offers.

Miller sums it up nicely: “One sale doesn’t make a market.”

Boards Butting In

Once a deal has been reached, can your co-op or condo board short-circuit your sale? The short answer is yes. In a co-op, Marks reports that she has seen boards turn down a transaction based on the price being lower than they see values in the building. “It doesn’t happen often, though,” she says. “Boards don’t like to admit it, but they are trying to maintain high values in their buildings.”

Hardy points out correctly that most condominium association governing documents have a right of first refusal clause, which gives the board the right to buy your unit at the same price you would sell it, if the board doesn’t want to approve the sale. In the event an agreed price was too low, the board could buy the unit for that price and try to sell it for more. But the board also might end up selling it for less.

In the end, pricing, like valuation, is both an art and a science. Marks suggests the following to anyone seeking to obtain the services of a listing agent to sell: “First, they must see the place. Second, the seller must get a survey of opinions and take the advice of professionals. Third, make sure the unit is properly marketed and properly priced.”

The broker you choose should be experienced in your market and building. Ask for credentials, references, and a history of successful transactions!

AJ Sidransky is a writer/reporter at The Cooperator, and a published novelist.

Leave a Comment