Seward Park Cooperative on the Lower East Side of Manhattan (where this author has lived for the last 15 years, and has served on its board of directors for the last six) is a remarkably diverse community of 5,000 or so New Yorkers that prides itself on its culture of neighborliness, service, and coming together in times of crisis. Residents have supported each other through blackouts and gas outages, rallied together after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, and carried water and supplies to elderly and homebound neighbors during days without heat, electricity, or running water after Hurricane Sandy. On days not marked by crisis, there are communal picnics and potlucks, swap meets and service exchanges, and organized events for all age groups. Lifelong resident and long-time board member Karen Wolfson calls Seward Park “our little village in the big city.”

When the specter of coronavirus initially appeared, it did not immediately seem to be another potential test of our strength as a community. At the end of February 2020, the Seward Park board was beginning plans for its usual spring and early summer events: the 10th year of its popular Hester Street Fair...a yearly party for residents called Summerfest...and the annual shareholders meeting and board election that normally takes place in early June. Like most communities in this part of the world, we were proceeding with business as usual.

On February 28, I got the following text from our general manager Frank Durant, VP of Lower Manhattan Real Estate for Charles H. Greenthal & Co.: “What do you think about temp Purell stands for each elevator bank? That’s only 12 units and they can be removed after and used during flu season in the future.”

On his suggestion, we had already installed extra sanitizer and cleaning supplies for our complex’s children’s playroom, community room, and gym, since it was becoming clear that the novel coronavirus was not going to stay confined to Asia and Europe. That same day, Durant sent shareholders and residents the first of what is at the time of this writing a series of a dozen memos titled “Measures to prevent spread of infectious diseases (Coronavirus).”

That was exactly one month ago. In the ensuing weeks, the world has turned upside-down, the time marked in my mind by the measures the co-op instituted to protect residents, vendors, staff, and visitors. Week 1: we stocked up on supplies; increased sanitizing schedules; alerted residents to CDC protocols (e.g., encouraging use of elbows, hips, and knuckles for opening doors, pressing buttons, and greeting others). Week 2: we introduced the concept of social distancing; asked residents to limit visits to the management office and hold off on non-emergency maintenance requests, move-ins/outs, or deliveries; discouraged large gatherings.

Beware the Ides of March

By the start of Week 3, Governor Cuomo had declared a state of emergency in New York, and Mayor De Blasio shut down all events and venues involving more than 500 people—including Broadway shows, concerts, and museums—and cut the legal occupancy of the city’s bars and restaurants in half. Following suit, the Seward Park board decided to shut all communal rooms and cancel any private events scheduled on the premises. We suggested that residents postpone any non-emergency contractual work, and began to enlist them in outreach to the many elderly, infirm, and otherwise vulnerable in our community. In conjunction with management, we compiled a list of residents willing to help out with operational needs in the event that a critical number of staff were unable to come to work because of their own illness, that of a family member, transit shutdown or other travel restriction, or executive shelter-in-place order.

There were certainly shareholders who balked at the idea of losing access to an amenity that they pay for monthly. Several others did not take kindly to delaying their already costly apartment renovations. One resident took issue when her request to hold a 100-person wedding in a communal outdoor area was denied. But, true to history, the vast majority of Seward Park cooperators understood the reasons for the measures and abided by them without complaint. Even more heartening, even with the prospect of being enlisted to remove trash, clean and sanitize hallways, and conduct stairway patrols, a significant number readily signed up for the various volunteer requests.

Being that we are a Naturally Occurring Retirement Community (NORC) with over 40% of shareholders having acquired their apartments between 1959 and 1996 when the co-op was a government-regulated redevelopment company, a significant segment of our population is older, and therefore particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. Many already receive services from organizations like Meals on Wheels, the United Jewish Council of the East Side (UJC), and the neighborhood’s older adult services run by the Educational Alliance. As those agencies curtailed or suspended their services altogether in response to the pandemic, our enlisted volunteers sprang into action. They were supported by the ingrained culture of neighborliness that calls upon residents of each floor to ensure that any neighbors in need are provided necessary resources or referred to management for assistance. The generational and economic diversity of our membership often enables us to function as a true cooperative—which in times of crisis is a literal lifeline.

Grave New World

By March 16, the World Health Organization (WHO) had declared the virus a pandemic, New York City closed its entire public school system, and many businesses across the city and elsewhere started asking employees to work from home in an effort to increase social distancing. Also on this date, Durant distributed update #5 to the coronavirus memo to Seward Park’s residents, informing them that the board had decided to close the two outdoor playgrounds between our four residential buildings, cancel all open houses and apartment showings, and suspend the Sabbath function of the complex’s 24 residential elevators that allows for one in each bank to automatically stop on every floor during times when pressing electronic buttons is forbidden for observant Jews.

With much of our population now more or less confined to the premises, the need for neighbors to support each other while respecting social distancing became at once more necessary and more complicated. The increased number of residents working from home, self-isolating, and/or quarantining coincided with the hundreds of school-aged children at home with nowhere to go; perhaps unsurprisingly, complaints about noise became more frequent. The earlier suggestion of delaying work on individual apartments was upgraded to a full stoppage order to reduce some of the noise-induced anxiety that many residents were experiencing.

Meanwhile, the co-op was undergoing years-long exterior maintenance and repairs work stemming from findings in its Cycle 8 Local Law 11 inspections, which also contributed to the disturbances now inflicted upon homebound residents. As the Department of Buildings had not yet offered guidance on how such mandated work would be handled under social distancing and stay-at-home orders, we opted to proceed with whatever would hopefully cause the least amount of disruption. At the very least, workers were spaced far apart, and did not need to access the buildings’ interiors—but it’s hard not to produce dust and noise during brickwork.

Inside the buildings, management and maintenance staff began working on staggered schedules and separating from each other, in case members of one group became infected and the rest had to self-quarantine. An unoccupied apartment that the co-op had purchased as a right of first refusal was converted into a makeshift dormitory for essential management and maintenance staff to stay in during double shifts, or in case of tighter citywide shutdowns. Staff in more high-risk age groups or with underlying health issues were sent home, with leave or vacation pay in accordance with an agreement reached between the building service workers union and the Real Estate Advisory Board. Ever the dedicated manager, Durant himself remained on-site to deal with the normal daily operations, as well as the minute-to-minute changes and decisions the community was being faced with.

In order to protect the dozens of volunteers who were now delivering meals, doing grocery shopping, and performing errands for other residents, as well as our essential staff who were still regularly cleaning and sanitizing common areas and entering apartments for emergencies, Seward Park purchased (at unconscionably inflated prices) a veritable stockpile of masks, gloves, protective suits, and disinfectants from a Bronx medical supply distributor and issued explicit instructions for their safe and effective use as staff and volunteers carried out their tasks. The co-op donated a large portion of the stockpile to local hospitals as well.

In observation of social distancing guidelines, the board began conducting its twice-monthly meetings via teleconference. Sellers and purchasers made use of Skype to carry out closings, with the attorneys and closing agent being the only ones permitted to be physically present. Management made the year’s board meeting minutes available digitally so prospective purchasers and their attorneys could review them without having to visit the office, and the board also moved to conduct future screenings via video conference.

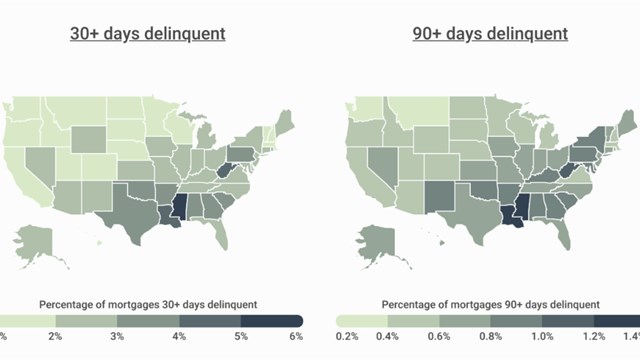

It was especially important to maintain these functions, since flip tax income from apartment sales represents a significant portion of the co-op’s operating budget. As many of our commercial tenants began to reduce business or close altogether, future rental income was in question. The same would likely hold true for shareholders losing their means of income and eventually being unable to pay their carrying charges and/or their mortgages. The Seward Park board is currently addressing these issues with our legal counsel, and assessing them in conjunction with any relief that comes from federal and state authorities.

28 Days Later

The final week in March was full of acts of heroism, as well as heartbreak. With the governor’s stay-at-home executive order for all nonessential workers going into effect the evening of March 21, beloved stores and restaurants already operating on thin margins began to shutter. Normally lively streets and parks saw mostly masked people, keeping cautious distance from one another. Fear and tension seemed to escalate, around the community and in our buildings themselves.

Around this time, the co-op also received its first confirmed reports of positive COVID-19 cases among its residents. With a population of our size and a citywide estimate of 1 in every 1,000 New Yorkers testing positive at the time, it was inevitable that we would see cases within our walls. By the middle of the week, we were also seeing our first COVID-related deaths.

In the new quiet that envelops the city, the sounds of ambulance sirens are all the more noticeable—and more frequent. We know when the high-pitched wail gets louder and then deepens and stops, that someone nearby has a critical case of COVID-19, as virtually no one goes to the hospital anymore unless their condition is life-threatening. But despite all the distance and despair, there is a swelling of compassion and camaraderie. No longer able to convene in restaurants and bars, New Yorkers have taken their socialization online, creating means of educating, entertaining, and even exercising with each other from the confines of home. Nightly #ClapBecauseWeCare rallies are bringing residents to their windows and balconies at 7pm each evening, where we can wave to neighbors and shake off some cabin fever while paying tribute to those on the front lines of hospitals, grocery stores, deliveries, and in our own buildings and grounds with applause, cheers, and music.

Like all buildings and communities in New York, Seward Park is adjusting to this new normal day by day. And I am proud to say that the co-op is doing so the same way it always has: with its usual heartwarming display of eagerness to help, contribute, and cooperate.

Darcey Gerstein is the Associate Copyeditor for The Cooperator, and a resident and board member of the Seward Park cooperative in New York City.

Leave a Comment