Plumbing is one of those things we take for granted yet without it, we might as well be back in the Stone Age. With dozens, hundreds and sometimes thousands of people living in individual co-op and condo complexes, the importance of well-maintained indoor plumbing grows exponentially.

The more each resident, manager and board members knows and understands about your building’s plumbing, the better the system will work. From the mechanics of plumbing in a high-rise building to the tips and hints on making the system flow—there’s a lot to learn about what keeps water working on our side.

How It All Began

Climb into the Wayback Machine, won’t you, as we travel through time to glimpse the origins of indoor plumbing. According to a series of articles published in Plumbing and Mechanical Magazine, the ancient Minoans hold the honor of being the first civilization with a flush toilet, located within the walls of the Palace of Knossos. While we do not know if the royal family ever stashed copies of the Minoan National Enquirer behind the seat, we do know that the world would not be flushing again for another 4,000 years.

With the introduction of lead pipes and increased engineering skill, the Romans took plumbing up a few notches with fresh water (thanks to an awe-inspiring system of aqueducts), heated floors, grand bath houses, dams, drains and sewer systems. Blame the marauding Visigoths for regressing us back to the Stone Age, however: by the 1600s, we were back to emptying our chamber pots in the streets, a trick that didn’t do much for sanitation and public health.

Across the Atlantic, New Yorkers were not faring much better. Chamber pots, outhouses and frequent trips to the town pump for water made up most of the plumbing options until the 1700s. A wooden pipe system was in place in New York by the early 18th century with underground sewers for storm water arriving on the scene a few years later. The early 1800s saw construction of a public waterworks system and the city unveiled the Croton Aqueduct System in 1842. By 1857, engineer Julius W. Adams designed the framework for the modern sewer system, which he put into practice in Brooklyn.

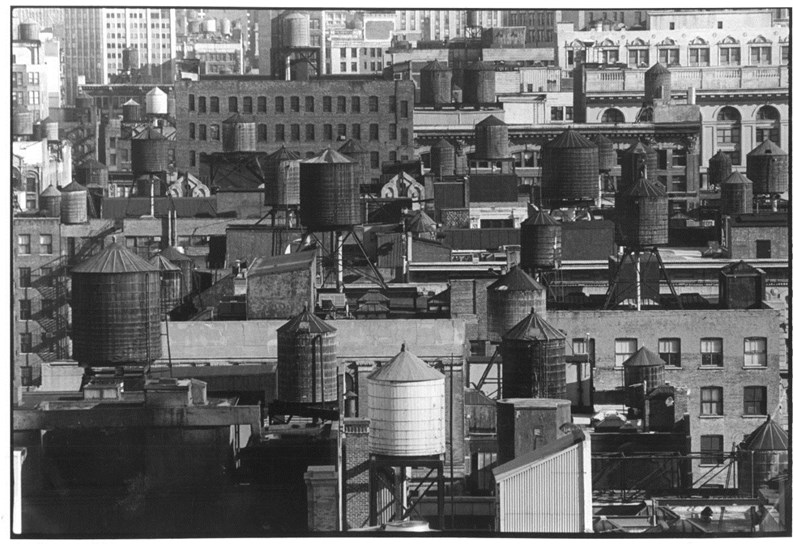

In 1845, a hotel in Boston became the first to offer indoor plumbing, thanks to a system where water was stored on the rooftop and distributed via gravity to guests. A steam pump was used to raise the steam water to the roof, a pre-curser to today’s gravity-fed tank system.

From there, the ball was rolling. By the 1900s, more and more Americans were enjoying not having to traipse across the yard to the outhouse in the dead of night. The outhouse was becoming a thing of the past – and quickly. From 1929 to 1954, purchases of indoor plumbing equipment rose more than 350 percent.

Here and Now

Today, most of New York’s co-op and condo buildings use one of two systems to provide water and sanitation service to its residents. With gravity-fed tanks, city water comes in to the building under regular city pressure, then goes through booster tanks which propel the water to rooftop tanks. From there, gravity feeds the water down to the units below.

With a pressure tank system, the water comes in to the building and proceeds into pressure tanks located in the basement. These tanks are pre-pressurized to a certain level, always maintaining a reserve of 2,000 pounds. Some older buildings in New York use both systems, while others only use one. Other buildings may use city water pressure for the first few floors, then one of the mechanical systems for the higher floors.

Newer buildings tend to rely more on the pressure system, which can be more easily maintained. “If one tank goes, they have separate valves that allow you to repair one tanks at a time,” says Henry Billharz, co-owner of Billharz Plumbing Inc., in Woodside. The pressure system is also easier to add to buildings when changes are made to the plumbing system. For example, if buildings decide to install new appliances with different water flow needs or if buildings decide to start filtering water or add a reduced pressure zone valve, which prevents back flow into the city water system, having a pressure system means all that all the certified plumbing crew may have to do is add a new valve or two.

When it comes to repairs, though, “[The advantage of] the gravity system is simplicity. As long as you can get the water to the roof, gravity will do the rest,” Billharz says. “In pressure tanks, bladders can break. Booster pumps can go out. Those pumps need to be greased and maintained regularly.”

As for the tanks themselves, Billharz says that pressure tanks remain relatively maintenance-free throughout their 10 to 15 year life span. Roof tank tops need regular scrubbings and cleanings, but will last for 80 to 90 years.

Who’s in Charge?

When it comes to plumbing problems within the walls of a co-op or condo building, the question of who is responsible goes back to the governing documents. “It’s really a gray area,” Billharz says. “It all depends on the building, the board and the managing agent.”

In some buildings, everything within the walls is the responsibility of the board. In a smaller co-op or condo community, the resident may just be responsible for problems with fixtures or whatever is visible within the confines of their unit. In larger buildings, sometimes shareholders want to be in charge, from the valves in the basement on up. Often this is because they want to control how much work is done when it comes to repairs. “Sometimes management might just want to repair a problem,” Billharz says. “The resident might want to replace or upgrade parts.”

Water, Water Everywhere

Plumbing problems come in all shapes and sizes, inevitably causing stress and yes, fear, for those who are standing in the puddles. As with any mechanical system, age plays a large role in the onset of plumbing issues. “The older the building, the more problems,” Billharz says.

Corrosion plays a large role in the degradation of a building’s pipe system. “If the existing plumbing is made up of galvanized piping, you’re going to end up having to change those pipes eventually,” says Stuart Liben, owner of Metro Heating & Plumbing, Inc., in Brooklyn. “Sediment is going to be building up in those pipes, and eventually building up in old shower, bath and faucet fixtures.”

Geography also can play a part in how long a building’s plumbing system lasts. “Different lines get fed different water,” Billharz says. “Some areas of New York have more chlorinated water than others. The Jamaica Reservoir water is highly corrosive for Brooklyn and Queens. The Lower West Side has more chlorine, which means we end up adding more filters. The water in the Bronx seems to be better.”

Keeping Water Safe to Drink

New York City’s water quality in recent years has been exceptionally good and within acceptable parameters of state and federal health regulations for drinking water, according to information compiled by the city’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

New York City’s surface water is supplied from a network of 19 reservoirs and three lakes in a 1,972-square-mile watershed that spans Westchester County and upstate New York. The reservoirs combined have a storage capacity of 550 billion gallons. Water flows to New York City through aqueducts, and 97 percent reaches homes and businesses through gravity alone; the rest must be pumped to its final destination. Chlorine is added to the water to kill bacteria, and fluoride is added to help prevent tooth decay. Fluoridation began in 1966.

Located in Westchester, Putnam and Dutchess counties, the Croton system consists of 12 reservoirs and 3 controlled lakes. The largest, the New Croton Reservoir, can hold 19 billion gallons of water. The system normally supplies 10 percent of the city’s drinking water, but can supply more when there is a drought in the watersheds farther upstate.

The Catskill system includes 2 reservoirs and supplies up to 40 percent of New York City’s water. The Catskill watershed is located in parts of Greene, Ulster and Schoharie Counties, about 100 miles north of New York City and 35 miles west of the Hudson River. The remaining 50 percent comes from the Delaware system, in parts of Delaware, Ulster and Sullivan Counties southwest of the Catskill watershed. This system contains 4 reservoirs – the largest is the Pepacton, which can hold over 140 billion gallons of water — more than the entire capacity of the Croton system.

DEP has an extensive water monitoring program in place and the quality of water coming from the watershed is high and meets all state and federal standards. The water quality report notes that there are occasional problems related to discoloration and the presence of chemical byproducts known as haloacetic acids, nitrates, manganese, iron, and lead, which are constantly being sampled and monitored. Rusty or brown water is commonly associated with plumbing corrosion problems inside buildings or rusting hot water heaters. The problem can also arise from street construction or water main work being done in the neighborhood, according to DEP.

In addition to water monitoring, the system infrastructure, which is between 50 to 150 years old, needs to be continuously upgraded. As a result, DEP’s long-term capital plan contains nearly $9 billion in funding for water supply related improvements.

Keeping Problems at Bay

For a plumbing system, regular maintenance is the equivalent of eating right and exercising for people. Boards and managers can ameliorate the wear-and-tear of time by paying proper attention to the miles of pipe, dozens of valves and enormous tank systems that function within their buildings.

“Plumbing should be repaired as things happen,” Liben says. “If there’s a leak in a faucet, change the washer. If a toilet is running, it needs to be fixed. Hot water heaters should be flushed and maintained. If there’s a leak, investigate it because it will be bad for the plumbing and bad for the building if you just let it go.” Those problems could include buckling floors, rotted joists and decaying walls.

Letting leaks go can cost in terms of water loss as well. “You don’t want to waste water,” Liben says. “You just create problems for yourself with wasted water.” In addition to dealing with leaks promptly, Liben suggests installing low-flow toilets and other water-reducing appliances and equipment to cut down on the water bill.

For many of the issues that arise with a building’s plumbing, a good superintendent can repair them without much of a problem. He or she also can serve as the eyes and ears, keeping on alert for potential problems. “If you have a good super, he can see corrosion building up on pipes,” Billharz says.

Your super can also make sure that valves are properly labeled. If major leaks arise, mislabeled valves can become a significant problem, forcing plumbing companies to shut down water in the entire building instead of in individual areas to make repairs. Often, this valuable information is lost as it is passed from person to person. “When you change supers or agencies, everyone leaves with a little more knowledge than the next person,” Billharz says. “I’ve seen instances where water damage could have been prevented if valves had been properly labeled. A good super is really worth his weight in gold.”

Bringing in the Pros

So when is it time to call in the big guns? When leaks are causing damage behind walls. Professional plumbing crews are able to go into buildings with the right tools in hand to cause the least amount of inconvenience possible. After cutting small holes in the wall, “We go in with small glasses and mirrors to locate the source of the leak,” Billharz says.

“You’ll need a plumber if there’s a large stoppage in the building that can’t be handled with small equipment,” Liben says. “Also for things like replacing toilets and pumps, adding fixtures or reconfiguring a bathroom.”

And it pays to call in professionals. Billharz says he has seen instances when unit owners have forgotten major plumbing musts – installing toilets without outlets or tiling entire bathrooms, then deciding to move pipes.

In the end, the key to good plumbing is maintenance. Keeping an eye out for problems before they start can save time, money and stress later on, something all of us can appreciate.

Liz Lent is a freelance writer and frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

Comments

Leave a Comment