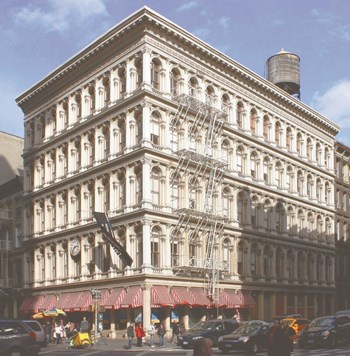

Today’s SoHo is synonymous with world class dining, prestigious art galleries, chic clothing stores, luxury boutique hotels, trendy lounges, picturesque cobble stone streets and stunning cast iron architecture.

The Lower Manhattan neighborhood SoHo is shorthand for South of Houston, the first official acronym given to a New York City neighborhood. Others eventually followed, NoHo (North of Houston), Tribeca (Triangle below Canal Street) and Dumbo (Down under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass.)

The neighborhood stretches roughly from Canal Street to Houston Street and lies between the Hudson River and Lafayette Street. Nearby neighborhoods include Greenwich Village, Tribeca, Little Italy and Chinatown.

SoHo has a colorful past and rich history and the area has undergone extreme changes.

Radical Transformations

In the 1700s’ SoHo was subdivided into sprawling farms. Broome Street, between Thompson and Greene Streets were covered with trees and peppered with rolling hills and streams. Beekman’s swamp (yes, a swamp) encircled Spring Street, and Bayard’s Mount (named after Nicholas Bayard, the 16th mayor of New York City) was the highest point in Manhattan, located west of Broome Street.

The early 1800s’ was a grand period in SoHo history. The upper class residential neighborhood was populated by an array of prominent and wealthy New Yorkers. The area was teeming with shops, theaters, hotels, stately mansions, minstrel halls and gambling casinos, especially along Broadway. In the mid-1800s upscale stores such as Tiffany & Co. and Lord & Taylor set up shop in the area. During this time SoHo had more bars and brothels than any other part of New York City.

Cast Iron Heyday

Roughly between 1840 and 1880 cast iron buildings were being constructed at a fast and furious pace. Pioneer architects Daniel D. Badger and Griffin Thomas led the way in this American architectural phenomenon. Approximately 250 cast iron buildings stand in New York City and the majority of them are in SoHo.

Originally, the inexpensive cast iron was used as a prefabricated cover over existing buildings with the intention of attracting new commercial clients with its newly modern façade. In addition to revitalizing older structures, cast iron was also cheaper than stone or brick. The buildings could also be built efficiently and quickly, in some cases, as little as four months.

Since cast iron was pliable, it could be easily bent and molded, and as a result, intricately designed window frames were created by craftsmen. The strength of the metal also allowed these frames considerable height and permitted high ceilings. Sleek supporting columns were added and interiors became more expansive. The spaces were now flooded with natural sunlight through newly enlarged windows. Gone were the days of dreary gas-lit interiors.

This explosion of commercial activity attracted million dollar textile industries, small firms, import/export houses and factories, but it also prompted wealthy residents to flee the area. Many of area’s wealthy residents found refuge uptown.

As commerce settled into the area, bordellos became common and during this time and Soho became home to the city’s first red light district. Two of the most popular houses of ill repute were located at 119 Mercer Street and 76 Greene. The brothels were patronized mainly by Southern merchants and planters who had to be recommended in order to gain entry.

Hell’s Hundred Acres

By the turn of the 20th century the area had drastically declined. The area was rife with sweatshops and factory owners illegally employing minors and immigrants with little pay to work in horrendous conditions.

In 1960, New York City Fire Commissioner Edward F. Cavanaugh Jr. nicknamed SoHo ‘Hell’s Hundred Acres’ (The term was widely used during World War II to describe a difficult battleground) because of the epidemic of accidental fires that swept through the area. The fires were fueled by the wooden floors and beams in the factories that were usually loaded down with highly flammable items such as clothing that would spread rapidly. SoHo had officially become an industrial wasteland.

In 1962 the New York City planning commission issued a report titled “The Wastelands of New York City,” and SoHo was characterized as an enormous commercial slum filled with run-down lofts and warehouses.

The report proposed demolishing the area to make way for the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX.) The ambitious Robert Moses project was intended to create an auto and truck through-route connecting the Manhattan Bridge and Williamsburg Bridge on the east with the Holland Tunnel on the west.

The plan was met with fierce opposition from local civic leaders, the young preservation movement, architectural critics as well as SoHo residents. New York City Mayor John V. Lindsay officially put an end to the highway plan in 1966.

The Burgeoning Art Scene

Many New Yorkers viewed the area as an industrial wasteland but artists saw an opportunity in the large unobstructed spaces, large windows admitting natural light and low rents. Artists such as Phillip Glass, Twyla Tharp, Chuck Close and Frank Stella, among others flocked to the area, transforming the once urban wasteland into a hipster, avante garde destination teeming with art galleries, performance art spaces and cafes. Shortly after, the SoHo cast iron historic district was created in 1973.

In the 1980s’ and ‘90s SoHo began to once again attract affluent residents and property values soon skyrocketed.

SoHo is also a frequent backdrop for movie and television locations and fashion shoots.

While strolling through the Lower Manhattan neighborhood today you might catch a glimpse of Academy Award winning actress Sandra Bullock, rocker Jon Bon Jovi, talk show host Kelly Ripa or comedian Tracy Morgan, in addition to host of other celebrities, artists and musicians who all call SoHo home.

Christy Smith-Sloman is a staff writer and editorial assistant at The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment