While news of defaults, liens, and other financial train-wrecks have dominated the news and caused many building boards plenty of sleepless nights, co-ops have been lucky. While a spike in defaults on maintenance payments over the last three years has forced many condominium boards to scramble to make up for lost income, legal and management professionals say that co-ops have survived relatively unscathed. But why is that?

Luck, or Planning?

Actually, luck has little to do with it, according to attorney Dennis DePaola, executive vice president of Manhattan-based Orsid Realty Corporation, which manages 120 buildings, around 80 of which are co-ops. “There are a lot of mortgage foreclosures, but not by co-ops, because co-op boards have been more diligent through the years in restricting their amount of financing. Co-ops are not typically over-leveraged.”

Another advantage co-ops have over condos is their priority over bank loans in order of payout in a foreclosure, says attorney Stephen M. Lasser of the Condominium & Co-op Group in the New York office of Stark & Stark, where he is a partner. “In a condo, the mortgage gets paid first," says Lasser. "If the owner doesn’t pay their common charges, it doesn’t really affect the lender. So the lender has no incentive to pay the common charges.”

A co-op, on the other hand “has a statutory lien,” explains Lasser, “and that has priority over the bank. If somebody doesn’t pay their mortgage in a co-op, in most cases the bank will step in and pay the arrears in order to prevent their lien from being wiped out if the co-op sells the apartment.”

Additionally, says to Steve Osman, CEO of Metropolitan Pacific Properties, a management company in Manhattan, “Condominiums are very hard to foreclose on. It could take years. Co-ops are rather easy. You’re just calling in common stock.”

But while the recession has not dramatically increased the number of defaults in co-ops, it has taken a toll on their financial health in other ways. In buildings with flip taxes, the virtual standstill in resale activity has cut off that particular income stream. And those which have relied on income from commercial space—both retail and office—have been hurt by vacancies and rent reductions as well. Perhaps most damaging of all is rising taxes. With New York City falling deeper in debt, and with so many of its revenue sources melting away, property taxes are soaring.

Indeed, with these pressures taken into consideration, “Collection of arrears is more important than ever,” says Osman.

Laying a Solid Foundation

As one might expect in this economy, “The loss of jobs is the number one reason [residents] are falling into arrears right now,” observes Osman. The other reasons are the same as they ever were, including illness, death, bankruptcy and marital disputes.

However, Osman says the most pernicious cause for nonpayment is “holding up payments for lack of services,” which has a demoralizing and anarchic effect on the operation of the corporation. “That’s very dangerous,” he warns his boards. “That cannot happen!”

So how can boards and managers see to it that their residents stay up-to-date in paying their fees, or failing that, that the building doesn't get stiffed in the end if the bank forecloses on the resident's apartment?

“A lot is going to depend on what your proprietary lease says,” according to real estate attorney Martin Tenenbaum, a partner in Tenenbaum & Berger, a Brooklyn law firm.

“When you are drafting proprietary leases, you should always have some kind of mechanism to deal with constant arrears. Most of the proprietary leases I’ve seen don’t have a paragraph for consistent nonpayment.”

According to DePaola, Orsid Realty recommends that its co-op boards revisit their corporate documents during times of economic stress such as these, and update their proprietary lease to make their nonpayment policy clear. Late fees range from $35 to as high as $100, he says, and are issued after the 8th or the 10th of the month. Generally, $50 is a fairly standard amount for late payment fees. DePaola recommends that co-ops levy interest on any outstanding balance to reflect the administrative costs of collection.

“Some boards give management the discretion to waive late fees if there is a meritorious defense,” adds DePaola, or if the shareholder “has missed just one month and has a good payment history.”

On a related note, “Board members should not get too involved with the actual process of the collections,” warns Osman, but rather leave it to management and attorneys every step of the way. “Otherwise it gets pretty miserable to come to your elevator after work, and deal with these people. They should allow management to be the bad guy, the enforcer of the house rules.”

Which is not to say that boards should abdicate their financial duties or turn a blind eye to residents in arrears. “Boards have to be very fastidious,” adds Osman. “You can’t slack off.”

A shareholder on a tight budget might ask him or herself, “‘if I don’t pay my maintenance, or if I don’t pay my electric, which one is worse?’ observes Tenenbaum. It’s up to the board, he says, “to make it not so easy for a shareholder to withhold payments.”

Effective Strategy

According to Lasser, “The general protocol is, if someone misses a month’s payment they get a notice from management. And then, if they are two months or three months late [as stipulated in the proprietary lease], the co-op turns it over to their legal professionals.”

“What becomes problematic,” he adds, “is if the board doesn’t do anything. If they let it accrue for a year, or couple of years—if it balloons—by then, the person might not have the money. They might focus on it if you bring it to their attention earlier.”

Also, warns Lasser, “even though there is six-year statute of limitations on a contract claim, if you sit on your claim,” when you finally do bring it to court, “they will say that your claim is stale and they won’t let you collect the oldest maintenance.”

All the professionals agree that building administrators need to follow protocol uniformly with each shareholder to avoid getting slapped with a discrimination suit. “You can’t pick and choose who is going to go on legal and who is not,” says Osman. “You must have a set policy and make shareholders aware of it in writing so there is no misunderstanding.

And remind them once a year if you have to, in writing.”

The management also needs to follow the tenets of the Fair Debt Collection Act, the federal consumer protection law which narrowly proscribes the procedure for collecting debt, including rent and maintenance arrears. The law requires that notices be sent to shareholders within a specific time frame, alerting them of their right to dispute the amount owed. Lawyers for the co-op could be to subject to penalties for violating protocol.

At the end of the two or three month interval of nonpayment of maintenance, as stipulated in the proprietary lease, management should turn the case over to the co-op’s attorney, who will issue an eviction notice. Promptness is important, as the legal process can be lengthy and costly.

The shareholder has 10 days to respond to an eviction notice. Once they do, the court date is usually a week later. Most likely they will ask for an adjournment, which adds more than a month. “So before anything happens,” says Tenenbaum, “they are about four months in arrears.” All in all, it’s not uncommon for a judgment to take six to eight months. And at any time the shareholder can settle and continue occupancy.

“There are some residents who are constantly behind,” says Tenenbaum. “By the time they finish paying up what they owed, they’re already a month or two behind again. So they’re basically just paying twice a year.”

To Sue or Not to Sue?

Whether to sue a resident for nonpayment is a tough call in some cases. Initiating eviction proceedings with chronically delinquent shareholders each time they fall into arrears might be a waste of money. “You want to hold off suing for maintenance too often,” advises Tenenbaum, “because you build up a large amount of legal fees.” On the other hand, he adds, “if somebody is doing it on a constant basis, you might want to build up a record of having to sue them,” which could bolster a foreclosure case down the line.

If a shareholder in arrears is subletting their apartment, the co-op is entitled to collect rent directly from the subtenant when it begins an eviction proceeding. “That is completely legal,” says Osman. “The tenant starts paying the rent to us rather than to the owner, and we keep any surplus in an account.”

“If the shareholder has a loan,” Tenenbaum advises, “I would strongly suggest that the board notify the bank, because banks do not want you to be in default of your maintenance payments.” The bank will put additional pressure on the shareholder to pay, and, should the shareholder fail to do so, “in order to protect their interest they come in and pay the maintenance—to satisfy the outstanding arrears so when they close, they can get clear title.”

The service of an eviction notice quickly reveals the shareholder’s intentions. “The ones who are really in trouble will usually come forward and ask for forgiveness,” says Tenenbaum, “and ask what kind of plan they can work out. It’s not worth dragging them into court. After all, you don’t want possession of the apartment—you want some kind of payment.”

One common repayment plan takes a carrot-and-stick approach. The shareholder signs an agreement to pay current maintenance charges when they’re due, along with a portion of the arrears with each payment. Late fees accrue steadily, but if the owner sticks to the payment schedule, once the arrears are paid off the late fees are waived. If he or she doesn’t pay off the debt, the accrued late fees stand and the case goes to court.

As for shareholders who ignore late letters and the eviction notice, says Tenenbaum, “There is no reason not to sue them. And considering the delays in court, you really have to sue them immediately.”

The Co-op as Landlord

Because of the corporate structure of co-ops, shareholders do not own their apartment but rather are holders of shares in a corporation, from which they rent their apartment. As such, lawsuits aimed at collecting arrears are conducted in landlord-tenant court.

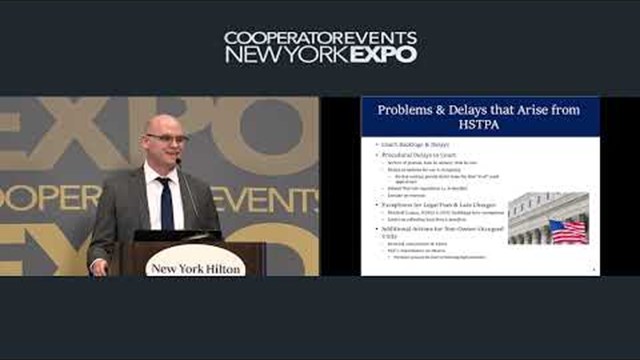

“When you are trying to collect money in a co-op,” explains Lasser, “there is a landlord/tenant relationship. You commence a summary proceeding in housing court for nonpayment of rent. Then you serve a notice of petition.” If the shareholder answers the petition, the court assigns a date for a hearing. The ideal and most expedient result of a court hearing would be an agreement on both sides to a structured payment plan, called a stipulation.

As for legal fees, advises Lasser, “If you enter into a payment agreement in court and can’t come to an agreement on legal fees, reserve your right to collect later. That way if the agreement does work out, or if a person decides to sell, you can probably recover the legal fees then.”

Of course, if the shareholder ignores the late letters and court summons, says Lasser, “you make an application for a default judgment and at that point get a warrant of eviction.”

Of the collection proceedings Osman's company has initiated, “About one-half come up with the money—either they'd always had it, or they get it, often from a relative. Forty percent of the time the bank that holds the mortgage on the person’s apartment pays the co-op—then works out a deal with the homeowner. And about 10 percent of them actually go to foreclosure.”

As landlords, co-op boards have a strong position in relation to shareholders. And considering the co-op’s lien priority over banks, says Lasser, “if you act quickly you really should be able to collect.” But you need to keep up your end of the bargain.

According to New York City’s Warranty of Habitability, explains Lasser, “if the court determines that the apartment or a portion of it is not habitable—if, for example, there is noise, a flood from an apartment upstairs, a roof leak or a bed bug infestation—they will give an offset to the maintenance charges just as they would with a regular tenant.

You’ve got to promptly make repairs and address concerns of individual shareholders, because if you don’t, they can end up getting a maintenance abatement.”

Even with most of the dirty work delegated to a management company and attorney, most board members would probably put collections at the top of their list of disdainful duties. But through it all, cautions Lasser, “It’s best not to have an us-vs.-them mentality.” After all, in a co-op, us is them.

Steven Cutler is a freelance writer living in New York City.

Comments

Leave a Comment