Though the practice may have slowed slightly since the apex of the housing market a couple of years back, condo (and to a lesser degree, co-op) owners still sometimes look to expand their own living space by combining two apartments into one larger unit.

Sometimes this is done at the outset of a deal, with the buyer purchasing two units with the express purpose of knocking down some walls, and sometimes it happens when an opportunistic unit owner hears that a neighbor is selling and snaps up that apartment to expand their own space. Needless to say, combining two distinct units into one presents certain challenges, both procedural and from an engineering perspective.

Why Combine?

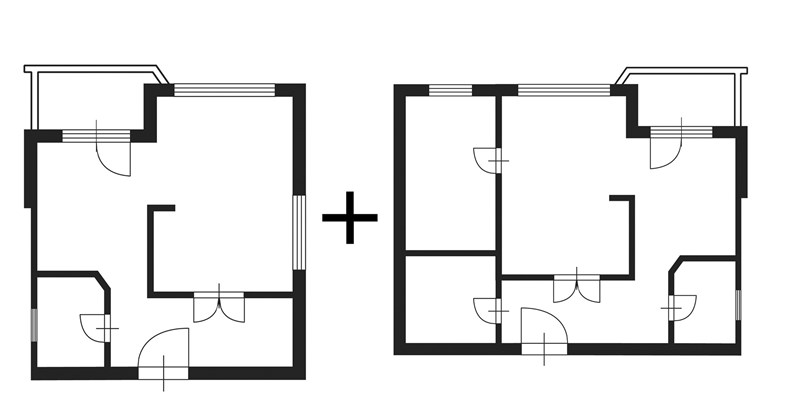

You own a one-bedroom apartment in a building you love. Then you have a kid. You don’t want to move, because moving with a baby is no kind of fun, and then something amazing happens: the owner in the adjoining one-bedroom apartment puts her apartment on the market (perhaps anticipating the baby noise), and you decide to buy it. By combining the two one-bedroom apartments into one, you have yourself quite a bit of space.

Anyone who’s ever lived in a New York apartment has at least daydreamed about this sort of fortuitous expansion. But how often does this sort of thing actually happen?

“It’s extremely common,” says Adam Finkelstein, a partner with the Manhattan-based law firm of Kagan Lubic Lepper Finkelstein & Gold, LLP. The reason why is as simple as adding one plus one and getting three. “The price of a three bedroom apartment is greater than two one-bedroom apartments that you can combine and make into a three bedroom apartment of a comparable size. That’s why a lot of people are buying apartments and then combining them. They get to buy cheaper, live there, and they’re creating more value. And we often have it where, not only are they buying two apartments and combing them, but they’re also combining hallway space in many instances.”

It may be common, and it may be logical, but that doesn't mean there are not hurdles to clear. The first, as with most projects in co-op and condo housing, is getting approval from the board.

Guardians at the Gate

“The hardest thing is convincing the board that [the unit owner] should be able to do this type of work,” says Perry Finkelman, founder and managing director of American Development Group LLC in West Hempstead, a construction consultant company. “In a co-op, you’re pretty much at the mercy of the board. They have the most control over your living arrangements and rules and regulations governing what you can and cannot do. It's less so in a condo, but when it comes to renovation, boards certainly can put some onerous restrictions on you which you must adhere to. So in both cases there are absolutely roadblocks.”

The borough where the apartments are situated plays some role in how easy the renovations will be, he says. “In certain neighborhoods—around Central Park, for instance—the building regimes are extremely, extremely finicky about any work being done. If you’re in Brooklyn, I think you’d have less of an issue with getting what you want done.”

Boards are not finicky just because they prefer to be finicky. One of their jobs is to make their building run as smoothly as possible, for the comfort of all unit owners and residents. And huge construction projects tend to fly in the face of comfort. “That’s going to be the biggest problem that any homeowner is going to be facing: the impact of noise and dust to your neighbors,” Finkelstein says. “And there will be complaints. There’s no way around it. It’s a communal living arrangement, for the most part. There’s no easy way of doing this type of work, and people will get inconvenienced.”

Measure Twice, Cut Once

After the board grants its approval, the next step is to devise the plans for the construction—and make sure they will not compromise the structure of the building. According to Ann Dadic, director of administration with Faithful+Gould, a global construction management company, “You’re also going to need a letter from the building’s engineer or a contractor, that by breaking a wall and combining units there will be no detrimental defects to the structure of the building.”

“If things don’t go smoothly, usually there’s an escrow amount,” she continues. “Let’s say you provide the board with a minimum estimate of $50,000 to remove a wall, cap a gas line, and remove a kitchen. Ideally that is what’s required to make two units into one. In every case, there’s an escrow amount that’s held back. That is at the discretion of the building. And if you do not meet the requirements of a successful combination knock-through, that money will not be returned to you after ninety days, or a hundred and twenty days… and I think the most flexible buildings will require the combination to be complete in six months. And if you don’t do that, that money won’t be returned to you. So there’s a financial holdback that can have a negative impact on you.” Dadic says that the idea behind these escrow requirements is to provide you with bottom-line incentive to finish the job as soon as possible.

As you might expect, there's quite a bit of proverbial red tape to cut through to get the process done. Happily, it’s simpler than it once was. “It used to be that you had to do a whole amendment to the C of O,” says Finkelstein. “An ‘alt-1’ filing is what it used to be called. Now they allow ‘alt-2’ filings, which are much more expedited. It’s a self-certification process. The difference there being that you’re required to remove the kitchen from one of the apartments, and you must keep both means of egress there. A lot of people will build stuff over that second doorway, or they’ll put a closet in front of it, so it’s not weird that you have another doorway into your apartment. What happens on the other side of the door is sometimes a gray area, but I know that you can’t just plaster over it in the hallway. But they definitely have to abandon one of the kitchens, cap the gas, cap the plumbing, and eliminate that in order to go under the alt-2. The only time they will allow you to keep the second kitchen is for religious purposes. Orthodox Jews can seek to have two kitchens, one for Passover and one for the regular time of year.”

Don't Cut Corners

In certain situations, the combination might seem so conceptually simple that you don’t want to go through the proper hurdles. It’s just a spiral staircase! It couldn’t be easier! What can go wrong! Plenty could go wrong—and has.

“If a unit owner builds something that is not permitted by the board, and there’s not a permit given, i.e. insurance,” says Dadic, “there’s going to be a lawsuit, and it could have a negative financial impact on the building. That will limit any shareholder’s ability to resell that unit. Most banks aren’t going to lend on a building that could potentially have a lawsuit that could impact the financial stability of that specific unit. So unless you get the proper approval and permits, you could not only be at risk financially, but you could also risk the other shareholders’ ability to resell their units.”

This is not just lawyerly speculation. Stuff does happen. “If there is construction above me, there’s the potential that they may break a pipe, and cause a leak into my unit,” she says. “This has actually happened to me personally. If that permit was obtained through proper procedures, then everybody’s covered. If it’s not, well, then the building and the shareholder have a big financial burden that they have to cover. Nothing in this world of construction or break-through renovation is ever 100% guaranteed, so there may be a normal, common mistake. In my case, the woman in the unit above, who bought the unit all-cash, ended up breaking a pipe, and my entire bathroom was flooded. It’s important that everybody knows what’s going on, so that you’re not the one holding the bag.”

Another issue that crops up is how to value hallway space. In many combinations, the construction requires that some of the public hallway space be appropriated by the new apartment, to combine them.

“The value of that space is always a hot topic, because the person buying it obviously wants it to be as cheap as possible, and the building selling it wants it to be as much as possible,” Finkelstein explains. “And there are all different theories as to how you value it. You can look at it like: ‘An apartment sells in the building for $1,500 a square-foot, and we’re selling a hundred feet, so it’s fifteen hundred times a hundred… that’s the price.’ And the purchaser will say, ‘Yeah, but the $1,500 a foot is for a finished apartment. This is just raw space. So it’s worth less.’”

Finkelstein continues; “The other way to determine price is to say: ‘Apartment A is worth $100,000 and Apartment B is worth $100,000. But combined, they’re worth $300,000. And you can’t combine them without this little piece. So there’s an extra hundred thousand dollars of value created, and you gotta pay for that.’ And another way to look at it is that, since nobody else can use this hallway space, so you’ll take whatever the person is willing to pay, because after all, it’s found money anyway. You can’t sell it to anyone else but that person with the adjoining apartments. So the valuation of that space becomes, many times, a very difficult formula.”

It can be worthwhile to do the combination. But it’s also enough of a headache that it’s sometimes best to move on. “My advice is, if you’re able to find a different unit that already has the space, in terms of how the unit works for you, that is probably a much better consideration,” says Finkelman.

Greg Olear is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment