In 1906, the dashing and amply-mustachioed Stanford White was shot dead by one Harry Kendall Thaw during a show at the Madison Square Roof Garden. Thaw was the jealous husband of one of White’s old flames, and the press dubbed the resulting court appearance “The Trial of the Century.” A century later, the lurid details of the trial are largely forgotten—but what is notable about the incident is that the victim, one of the most famous New Yorkers of the day, was an architect; it was White, in fact, who designed the old Madison Square Garden.

There are not many cities in the world where the death of an architect, whatever the circumstances, would trigger the Trial of the Century. But New York has always held architects in high regard. Perhaps no other metropolis is as synonymous with fantastic, innovative architecture as New York. But while many appreciate the grandeur of an edifice like Grand Central Station or the Chrysler Building, residential architecture - the buildings in which real New Yorkers actually reside—often gets short shrift.

We Live Here

It may not feel like it, but Manhattan is of course an island. Its 23 square miles include Central Park and other public green spaces, the jutted rock of upper Inwood, and countless miles of asphalt roads and sidewalks. When you subtract all of that, and take away the office buildings and municipal buildings and the Chelsea Piers and the Boat Basin and all those other areas of the island where people do not live, you’re left with a relatively tiny area in which to house some 1.5 million human beings.

“Manhattan,” as Luc Sante writes in his fascinating 1991 book Low Life: the Lures and Snares of Old New York, “is a finite space that cannot be expanded but only continually resurfaced and reconfigured. Manhattan is a wonderland of real estate speculation, a hot center whose temperature cannot but increase as population increases and desirability remains several paces ahead of capacity.”

Originally, only the lower tip of the island was an urban area. The streets and avenues that now form the city’s distinctive grid began as rural farm land. When Cornelius Vanderbilt built Grand Central Station, the name was scoffed at; the place was far uptown, neither grand nor central to anything.

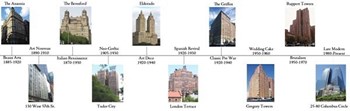

This was the canvas on which New York’s first architects plied their trade. Enormous lots, some comprising an entire city block, provided ample space for whatever they wanted to erect, and the era’s titans of industry had deep pockets to fund projects on a grand scale. The legendary Dakota Building for example, was completed in 1890 when the surrounding area was more or less vacant; the name Dakota was even a joking reference to the Dakota Territories, because when the building was built, the Upper West Side was so sparsely inhabited it was considered as remote as the Old West. To Victorian New Yorkers, the gorgeous example of North German Renaissance style might as well have been built on a dude ranch in Texas.

The collection of residential buildings built at this time—apartment buildings, as they were carefully referred to, to distinguish them from the more bourgeois flats in European cities—now known as “pre-war” could be as sprawling as the architect wanted. As a result, “pre-war buildings are bulkier, heavier, more ornate, with larger rooms,” says Howard Zimmerman, of Howard Zimmerman Architects in Manhattan.

“Pre-war buildings tend to have higher ceilings and moldings, charming details, and spaces divided into distinct rooms, as well as features like wood-burning fireplaces and multiple exposures,” explains Ken Scheff, executive vice president and managing director at Stribling & Associates, a Manhattan-based real estate brokerage firm.

There is a majesty to many of these old buildings. Many of them were built by rich people for rich people, at a time when nevertheless, it became financially unsustainable for one family to occupy a mansion on Fifth Avenue, as the Astors once did. Part of the yen for pre-war buildings is not just what they look like, but where they are located. “A lot are in the traditional, established neighborhoods,” Scheff says. If you want to live on Park Avenue, your options are limited (if that’s the right word!) to pre-war buildings.

“The prestigious streets”—Central Park West, Park Avenue, Fifth, Gramercy Park—“have retained their prestige, but people are looking at other areas.” Scheff points out “the extreme desirability of Brooklyn,” and notes that West Chelsea has become “a hotbed of architectural innovation.”

After the Wars

When the war came—the Second World War, that is—demand decreased, and new construction slowed to a trickle. When the war ended, demand for housing surged again, but architectural style was one of the many things sacrificed to the war effort.

“I think there was a period of great style and technological innovation up until World War II,” says Jim Davidson, a partner with SLCE Architects in Manhattan. “After World War II, New York, London, and other cities had a cash flow and housing crisis that had to be addressed.”

The post-war years ushered in a boom in new construction, much of it Modernist in style and utilitarian in aesthetics. “Post-war buildings are white brick and red brick,” says Davidson. “Off-the-shelf windows placed on off-the-shelf bricks. They ceased to be design exercises and are just building exercises—and they sell at a discount.”

Not that post-war buildings are all terrible. These newer buildings most certainly have their advantages, says Scheff. “Post-war buildings have larger windows, air conditioning, not as many dark rooms, more bathrooms, and good closets,” he says.

Generally speaking, the residential designs of the mid-century period have not aged as well as their more ornate forebears. It is an unloved period of architecture, where many charming older buildings were torn down to built straightforward brick towers that many consider dull, if not outright ugly.

“There are many good things about modernism, but when it extends to multiple dwellings, it just doesn’t hold up so well in the marketplace,” Scheff says. “Buyers don’t want minimal ceiling heights, tight kitchens, and tight bathrooms.”

Because of their uniform design however, post-war buildings are easier to modify. Inside a boxy column of white bricks could be something glorious. “From a brokerage point of view, the most important thing—even more important than pre- or post-war, is the quality of renovation,” says Scheff. “That’s a great equalizer. A buyer might have said, ‘I’ll never even walk into a white brick building,’ but now, they want to see something fully furnished.”

This has been part of an overall trend away from the more traditional, heavier, elaborate pre-war aesthetic. “Post-war is coming back into fashion, because people are starting to embrace mid-century furniture and design,” Scheff continues, adding that the old derision aimed at post-war residential buildings is lessening. Call it the Mad Men effect.

Build it Forward

As World War II recedes into the distant past, the “post-war” descriptor has expanded to cover more than the minimalist, brick-and-window buildings erected in the ‘50s and ‘60s. We are, right now, in the midst of a boom period for architecture.

According to Davidson, “Manhattan and the other boroughs have been going through a Renaissance of fantastic architecture since the 1980s. Buildings are being used to build their neighborhood, and neighborhoods are aggregating around an iconic building. They’re being revitalized because of an outstanding piece of architecture.”

There are many factors contributing to this new zenith.

The first: we have the people who can do it. “The reason New York has been such a hotbed of architectural innovation is because talented, interesting people come to live and work here,” says Scheff. “There are many tremendous architects in the city.”

Second, there is now great demand not only for new construction, but distinctive new construction. “The developers realized there is tremendous value in design, inside and outside,” Scheff says. “Property values here are very high, so it creates more value for the consumer if you create something new and beautiful.”

And while the cachet of living in a remarkable building is as old as Peter Stuyvesant’s peg leg, Scheff says developers are working harder than ever to generate cachet on new buildings. “Each building now invests a lot of energy on marketing—a theme or a persona of a building that sets it apart.”

“Everybody’s looking for an edge,” adds Zimmerman. At the end of the day, however, what makes a building special is the architecture itself. “Just because you put a name on a building doesn’t make it distinct. The look, the façade, the silhouette—they all come into play.”

Davidson is encouraged by the future of Gotham’s architecture. “It’s fortunate that the boom in design has coincided with a new means of analysis of what a building should look like and how a building should fit.”

One thing is certain: as long as there is a city of New York, there will be new buildings going up, many of them spectacular. “New York is always building,” Zimmerman says. “It’s a showcase for architecture.”

Greg Olear is a freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment