In the 1950s and 60s, airlines hired comely young women to work the aisles and tend to passenger requests—stewardesses, they were called. And while the word was the feminine form of steward, the combination of the title, the outfit, and the aiming-to-please job description seemed to exclude male participation. To this day, the word stewardess connotes a young, attractive, accommodating woman.

This was by design, of course. The airlines were trying to doll up air travel and give it some sex appeal. Along the way, they ran into some turbulence: there is nothing in the “stewardess” job description that could not be done by a man. While they wanted pretty young females to pass out peanuts and Pepsi, you do not have to be pretty, young, or female to open cans of soda. It was not a job requirement—in labor law lingo, a BFOQ, or bona fide occupational qualification. Therefore, discriminating on the basis of age and gender was deemed illegal. On flights today, you routinely see men and women of all physical descriptions instructing you to put your seat back to the upright position. \

And they aren’t stewardesses anymore. They’re flight attendants. A subtle, but important, distinction.

The same process is being played out, albeit more slowly, and with the genders transposed, among a different sort of uniformed union worker on the sidewalks of New York: the doorman. It’s a masculine word, doorman. Male bias is inherent in the phraseology. One imagines a tall gentlemen resplendent in long coat and cap, a regimental stripe on the side of each pant leg, his white-gloved hand extended to hail a taxicab, his elegant presence announcing to all passersby that the building at whose entrance he stands is a fashionable address. Indeed, since there were doors to man—or, rather, to tend to—the ones doing the tending have been men.

How, one has been conditioned to wonder, could a woman serve the same function? What would such a woman even be called? Female doorman doesn’t work; it’s like calling Hillary Clinton the Female Secretary of State. Neither doorperson nor doorwoman roll off the tongue very gracefully. And you can’t do for doorman what they do for chairman by simply shortening it to chair. To “flight attendant” and “postal carrier” the gender specificity, the National Organization for Women recommends using the term door attendant.

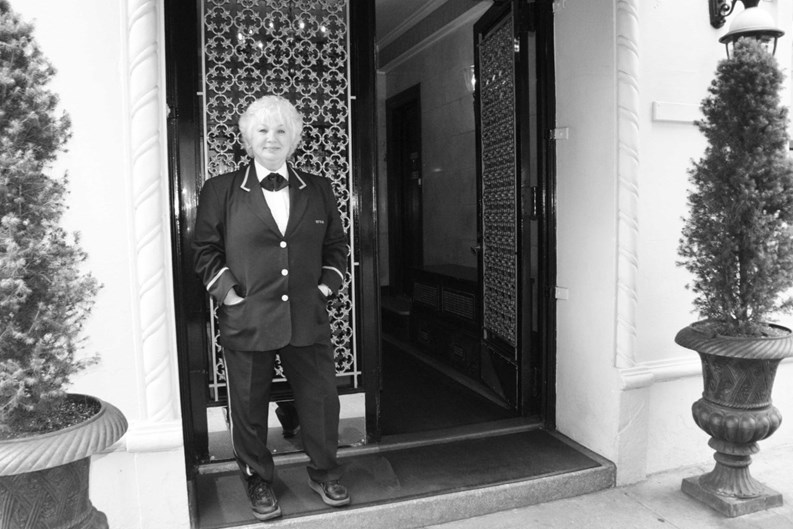

A Rare Species

In Doormen, his seminal work on the subject, Peter Bearman, says that the city’s first female door attendant was the wonderfully-named Sadie Sutton, whose hiring in 1971 caused such a stir that the New York Times saw fit to devote a lengthy article to her. Genders dynamics in the workforce changed radically in the ensuing quarter century—everywhere but in front of ritzy residences, that is. In 1997—when a woman, Madeleine Albright, was Secretary of State—the Plaza Hotel hired its first female door attendant, and again, this warranted media coverage. Thirteen years later, not much has changed at the door.

“It’s one of the last bastions where you don’t see women,” says Madeline Lee Bryer, an attorney who represented would-be door attendant Panathy Hill in her gender discrimination suit against a large property management company in the late 1990s. “It’s a shame.”

Aki Ito, researching a piece she wrote in 2008 for What NOW, the National Organization of Women’s journal, spent weeks trying to track down female door attendants and was “shocked” at how few she turned up.

The Service Employees International Union Local 32BJ represents the lion’s share of the city’s door attendants, but even they do not have an accurate count of how many—or, to be more exact, how few—female door attendants there are. “Over a third of the doormen we interviewed said that they had never seen a doorwoman before,” Ito writes. “Interviewing the doorwomen was more like an elusive treasure hunt, hoping that the doormen who told us, ‘I may have seen a woman on 80th and Lex, or maybe it was 60th and Lex, or maybe it was somewhere downtown,’ had remembered correctly.” Ito says she was able to round up just seven female door attendants. And, she notes, “I may have spoken to more doorwomen than anyone in the city.”

More Than the Door

Elizabeth Floody is one of the city’s handful of female door attendants. She’s worked at a co-op on West 86st Street for eight years, and the first thing she says, when asked about her line of work, is, “I love my job.”

This is a standard refrain among door attendants, male or female. The job is more than just carrying packages and hailing cabs. Door attendants are the face of the building and an integral part of the community. While they are not security guards, their collective presence on a city block, as Jane Jacobs explains in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, provides sufficient eyes on the street to help make a neighborhood safer.

“You’re part of the extended family,” Floody says. “You know mothers and fathers; you watch kids grow up.”

There is an obvious social element to the job. Door attendants are not tied to a desk, like concierges. They spend part of the day outdoors. The hours are flexible. And while the duties do not change from day to day, no two days are alike. “Every day is an adventure,” says Floody. “There hasn’t been a day when I wake up and think, ‘I don’t want to go to work today.’”

Then there are the perquisites.

“It’s a union job,” says Bryer. “There’s no special union requirements for the job. It offers health benefits. Many doormen really like their job.” She continues, echoing Floody, “They become part of the family of the building.”

The hardest part about the job might well be getting it in the first place. And that’s part of the problem. These are coveted positions, with very little turnover.

Floody calls her hiring “a fluke.” She was looking for work—she’d been employed as an assistant school teacher—and a part-time elevator operator position opened up in a building in which she had a connection with a board member. Eventually—and not altogether seamlessly; she met with some resistance at first—the part-time position led to the full-time post as a door attendant.

The Value of Diversity

So in an era where ironclad ideas of what is and isn’t “appropriate” work for either gender is viewed by most as a quaint anachronism, why so few female door attendants? The issue is less about whether women are qualified to be door attendants—they unequivocally are—and more about the recruitment process.

“Most of the positions are filled through word of mouth,” says Bryer. “Word of mouth is not, in and of itself, discriminatory,” but it does open up a can of potentially-litigious worms. “The jobs aren’t posted in newspapers,” says Bryer. “You don’t see ads in newspapers. You don’t see the listings. The jobs are not open to the general public.”

So who winds up with the positions? Quite often friends and relatives of the super, or whoever is in charge of hiring the door attendant.

“A lot of buildings have a super,” says one female door attendant, who preferred not to give her name. “They bring their family in. They all work together.” She is an outsider because not only is she the only woman on the staff, she’s also the only staff member who is not related to the super.

Nepotism is as old as employment, of course, and there’s no law that says you can’t hire your brother as a doorman. But if you don’t actively recruit others for the post, paying particular attention to the protected classes cited in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1962, you open yourself up to a lawsuit that you probably won’t win.

“Boards should be aware that they need to be diversified, both racially and male/female,” says Bryer. “That’s important for protection against lawsuits.”

This does not mean that you must hire a woman or a person of color to work in your building. But it does mean that you are compelled to recruit from a wide pool of candidates. If you’re hiring the only person you considered for your door attendant vacancy, and that person is your super’s brother-in-law, you risk exposing yourself to lawsuits. Incidentally, the suit Bryer brought for Panathy Hill was settled during jury selection. She is bound by a confidentiality agreement not to discuss the case, and didn’t; but it stands to reason that Hill would have prevailed.

So will the city’s door attendant ranks reflect more of a gender balance in the years to come? “I think it’s time,” Floody says. “We can do just as good a job as men can.”

For now though, a female door attendant remains a rarity. “There’s not a day that goes by that people don’t remark on it,” Floody says. “They shake my hand and say, ‘It’s nice to see a woman doing that,’ or, ‘I’ve never seen a doorwoman before.’” But the attitudes, it seems, are shifting. “Very slowly,” says Floody, “the doors are opening up.”

Greg Olear is a freelance writer, novelist and a frequent contributor to The Cooperator.

Leave a Comment